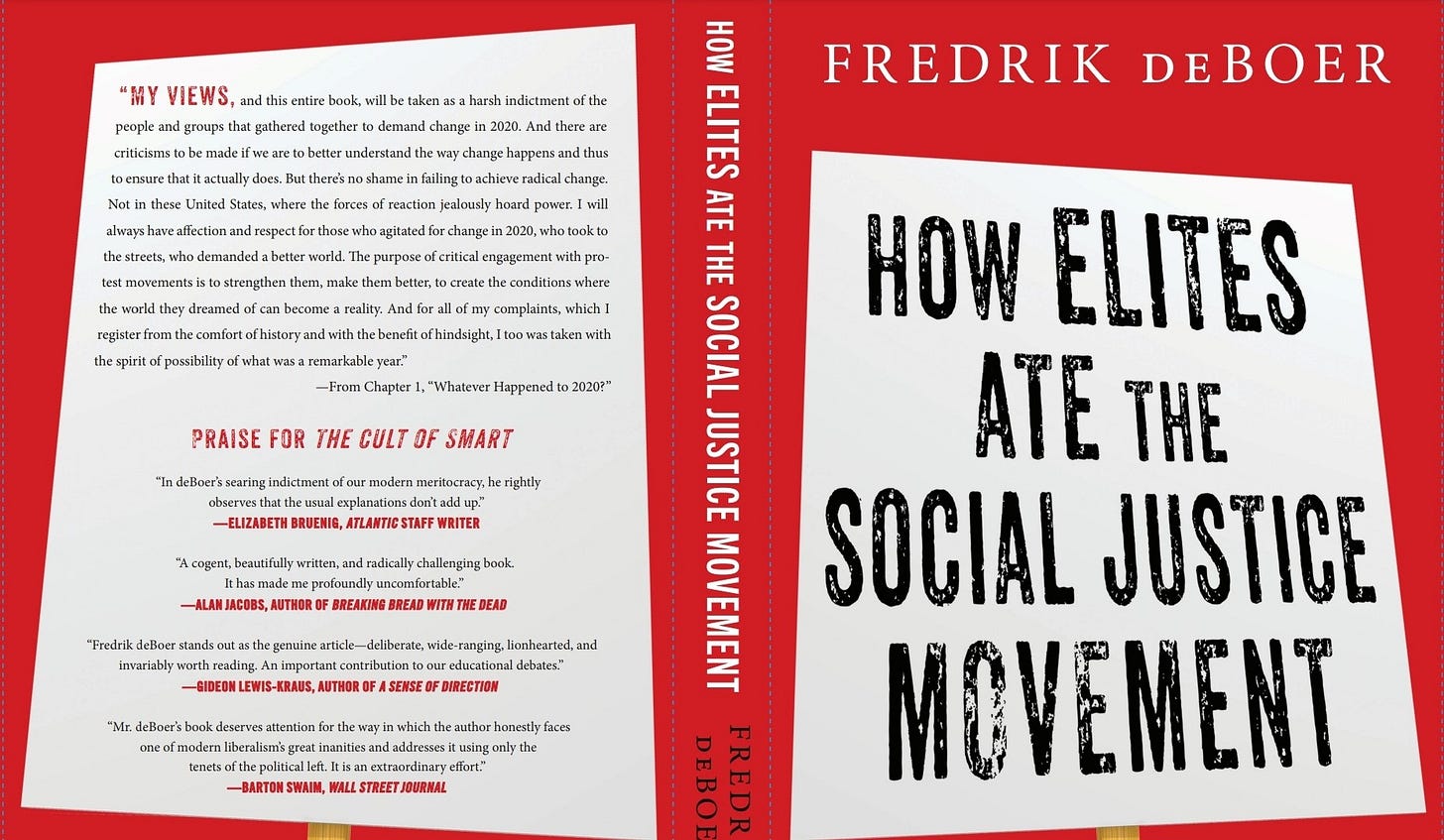

Review: How Elites Ate the Social Justice Movement, by Fredrik DeBoer

A clarion call for class-first leftism.

For a deeper discussion of this book, check out Hot Take Think Tank episode three.

Freddie DeBoer has written the book I wish I’d had when I was trying to figure out if it was possible to be a non-identitarian leftist—that is, someone who cares deeply about alleviating poverty and addressing material inequities but who doesn’t think fixating on identity, representation and language will get us there.

How Elites Ate the Social Justice Movement offers a clear-eyed examination of recent social justice movements and how they have failed to create lasting material change, before laying out a vision for building an effective leftist mass movement capable of delivering the goods.

DeBoer sets the stage by showing how leftists have been moving away from bread-and-butter issues and towards a myopic focus on the symbolic for quite some time. He shows how the Occupy protestors’ aversion to specific demands and their hostility toward structure kneecapped their potential to enact lasting change.

He also outlines the rhetorical battle between Hilary Clinton and Bernie Sanders for the 2016 Democratic nomination, wherein Bernie supporters were accused of being ignorant about racism and sexism, and Hilary appealed relentlessly to (non class-based) identities. This paints a picture of the left as we head into the Trump years: fragmented, misguided and hostile toward the working class.

It is within this context that DeBoer examines the racial reckoning of 2020, and why what was likely the largest movement in American history failed to secure any significant legislative reforms. He discusses the impossibility (and unpopularity among Black Americans) of abolishing the police and the mixed messages about how literally this demand was to be interpreted. He also illuminates taboos that hurt the movement’s credibility and potential for coalition building, such as the fact that by the numbers, more white people are killed by police than Black people, and that police killings are both exceedingly rare and still too common. But perhaps most importantly, he points out how abstract contemporary anti-racism has become:

“We have gone from marches on Washington to demand jobs and demonstrations to support striking Black garbage workers to millions of decent white liberals clutching “anti-racist” books on the subway, reading about why they’re wicked and should feel bad, ensuring that their next interaction with a Black coworker will be strained and awkward, and lining the pockets of white editors, white publishers, sometimes white authors in doing so […] Meanwhile, in cold apartments lined with lead paint, hungry Black children hide from the violence that grips their neighbourhoods. This is the reality of racial justice in 21st-century America.”

From there, DeBoer examines leftist debates about political violence, the successes and failures of the #MeToo movement, and the complicated relationship between social movements and the nonprofit industry. Did you know that, wage-wise, the nonprofit sector was the third-largest employer in the country in 2016, ahead of finance, retail and food service? I sure didn’t. DeBoer’s chapter on this industry is worth the cover price all on its own. Reading about the sector’s siphoning of righteous anger, talented organizers and potential tax money, and the perverse incentives that distort their priorities over time, gave me a new perspective on the nonprofit industry.

DeBoer’s most crucial message is that organizing around class is how the left can win big. Doing so gives us the numbers and the common goals that are necessary for success. Rather than fixating on language, we need to focus on creating specific policy goals, and then strategically employ whatever messaging can help us secure widespread support.

I once heard an excellent anecdote about this (although I can’t for the life of me remember where I did—if you recognize it, please let me know so I can link to the source). Say there is a racialized community that is struggling with a high unemployment rate. You could propose an employment centre for that racialized group, but you would face significant pushback from the public due to its exclusionary nature. Instead, you could propose an employment centre in that community’s neighbourhood that is open to everyone. Public resistance becomes unlikely, and the racialized community can access the employment services they require. What would you choose: a failed campaign that uses the language of race, or a successful campaign that uses strategic language to get the centre built?

One thing I really appreciated about this book is that DeBoer challenges the false dichotomy between class-based mass movements and campaigns that fight for the rights of minority populations. In fact, majority support is often a crucial factor in improving conditions for minority populations. In arguing for a class-first leftism, DeBoer is not saying that racism, sexism and ableism don’t matter, or that they should be secondary concerns. What he’s saying is that uniting and growing the left around class-based struggle will provide us the numbers and solidarity we need to fight for both policies that will benefit all working people (such as Medicare for All) and those that will address specific inequities (such as high Black maternal mortality).

I’m not sure when DeBoer submitted his manuscript for this book, because although he calls for a reinvigorated labour movement, he doesn’t seem to think it’s happening yet. Thankfully there’s more and more evidence that it is.

I also think the clickbait title doesn’t quite do justice to this book, which is less sensational and more pragmatic than the title suggests, although DeBoer said in an interview that the publishing company named the book, so I can’t hold it against him. Just know that this isn’t a screed or a manifesto; it is a lifelong activist’s thoughtful analysis of what’s impeding the left and what we can do about it.

I would recommend this book to anyone who’s trying to find their footing after leaving the social justice subculture, or anyone who’s felt alienated by the left. It would make an especially powerful gift to someone who’s got one foot in and one foot out, because DeBoer makes a powerful case that there’s a better way to fight for social and economic justice than dividing ourselves into smaller and smaller camps, and you can join in anytime.

Thanks - a very helpful summary (I'll buy and read the book) and it fits my own sense that class-first (but with an intersectional view of all divisions) is the most potent way to go. In England, where I come from, we make a distinction in the middle class realm to recognize that most of us, like me, are lower-middle class (working people with college ed like nurses, CPA's, junior managers and so on) who have been split from classic blue-collar working people to become system lackeys, differentiated from the senior managerial/coordinating class who are tightly bonded by aspiration to the owning class. I see the re-unification of the lower-middle class with the working class as the most do-able priority and this mostly means that us lower-middle class need to deconstruct the false sense of superiority that too much education of the wrong kind lays on us ... try rc.org for help with this ...

Well, there's goes another famous phrase out the window. You're bustin' up my game here, Andy.